Karen Stevens, University of Kentucky

The history of archaeology in the Green River Valley begins just over 100 years ago with a man named C. B. Moore and a steamboat called ‘The Gopher.’ A wealthy man and amateur archaeologist, Moore traveled throughout the southeast in the late 1800s and early 1900s digging up thousands of artifacts and burials from previously unexplored sites. While in Kentucky, Moore’s work on the Green River focused on a prehistoric phenomenon that continues to interest archaeologists today—that of a group of hunter-gatherers who lacked pottery and buried their dead near the river among heaps of shell.

A Photograph of the Gopher in 1900. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HAER, “HAER MISS, 44-COLUM.V, 3-43.”

The 1930s saw an increase in what we know about the Green River Valley Archaic sites due to large scale excavations conducted during the New Deal Era. In order to create jobs during the Great Depression, federal agencies, such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), conducted excavations at sites throughout Kentucky to create employment opportunities for out-of-work men. It was during this period that William S. Webb and William D. Funkhouser expanded our knowledge about the people who lived in Kentucky long ago.

Chiggerville (15OH1) Field Crew, Ohio County, Kentucky, WPA/TVA Archives, presented courtesy of the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.

So, what do we know about the lifestyle of the people who lived in the Green River Valley during the Archaic period?

Thanks to the continual efforts of past and present archaeologists, we now know a lot more about these peoples mobility, food ways, and material culture than we knew 100 years ago. For example, with the development of radiocarbon dating, we now know the hunter-gatherers used these shell “middens”—or trash heaps— for thousands of years (8,000 to 1,000 B.C.). We have also found that most of the occupation of these sites happened between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago.

Even though the sites were used for thousands of years, these hunter-gatherers would have certainly been mobile: traveling throughout the region during different seasons in order to exploit diverse resources. How do we know they were mobile? We know this because archaeologists have found little evidence of permanent house structures or food storage, things that are often signs of non-mobile lifestyles. However, movement around these sites would not have just been tied to gathering and hunting for food. These families would also move around for ritual and social interactions, including the burial of their dead, feasting, marriages, and the sharing of information with relatives and friends.

Cache of Stone Knives at Indian Knoll (15OH2), Ohio County, Kentucky, WPA/TVA Archives, presented courtesy of the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.

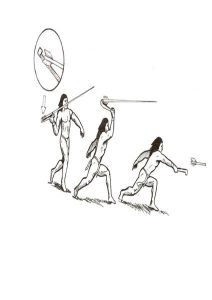

Common features at these sites include stone stools and spear points, hearths and fire basins, and food waste (ex. deer bone, shellfish, and nutshells). The hunters’ tool of choice for killing deer would have been the atlatl, or spear-thrower. Sometimes they would even stash several stone tools and spear points together for later use. Archaeologists call these caches. The hearths and fire basins were probably used for cooking of the food that was caught or gathered. These hunter-gatherers focused their diets on the hunting of deer and other small mammals; the fishing of water-related resources, like catfish, freshwater shellfish, and turtles; and the gathering hickory nuts and other plant foods, like squash and goosefoot. Archaeologists have also found other artifacts, such as pestles, hammerstones, and grooved axes, which would have been used to process plant foods and help with the making of spear points, among other things.

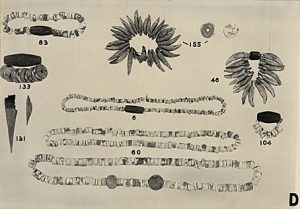

The Green River Valley Archaic sites are unique because they have one of the largest pre-Columbian human burial populations. Indian Knoll alone had over 1,000 burials. Through the study of these burials, we know that although the hunter-gatherers were likely egalitarian (or had equal freedoms), there was some social differentiation as seen by only some people having grave goods. However, status was not restricted by sex or age—men, women, and children can be found with artifacts in their burials. Artifacts associated with burials include things mentioned above, like spear points, pestles, and atlatl parts, but they also include personal accessories such as shell gorgets, beads, and bone pins. And unlike the common extended or flat position people are buried in today, these prehistoric people usually buried their dead wrapped up in a coiled or fetal position. Some burials even show evidence of violence like injuries from clubbing or spear points embedded in bones. These injuries indicate that as hunter-gatherer populations grew competition for resources and space caused fighting.

Shell bead and animal tooth artifacts likely worn as personal adornments, Carlston Annis (15BT5), Butler County, Kentucky, WPA/TVA Archives, presented courtesy of the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.

While the way of life of these mobile hunter-gatherers may seem unlike our own, they were still human, just like us. They were interested in exotic things, with materials like copper from the Great Lakes region and marine shell from the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts showing up in the ancient trash piles. They were interested in decorating themselves with shell and bone jewelry. They also showed great reverence for man’s best friend: dogs! Dog burials are found throughout this area of the Green River Valley. Sometimes dogs are buried with humans, but often times they are buried alone with the same care and respect a human would receive during burial. It is through the careful excavation and analysis of sites like these that archaeologists are able to help us connect with humans that lived thousands of years ago in the places we live today.

Dog Burial at the Ward Site (15McL11), McLean County, Kentucky, WPA/TVA Archives, presented courtesy of the William S. Webb Museum of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.