Brian Mabelitini and Donald Handshoe, Gray & Pape

Scott Clark, detecting.us

Background

The Goodnight (also spelled Goodknight) Cemetery is a small family cemetery located on private land approximately two miles north of the City of Perryville in Boyle County, Kentucky. The cemetery was likely founded in 1841, with the death of John Goodnight.

Following the October 8, 1862, Battle of Perryville, the home of Jacob and Susannah Goodnight was taken over by Confederate troops for use as a hospital. The two main field hospitals were Antioch Church, which housed Union patients, and the Goodnight farm, which held the Confederate wounded from Major General Benjamin Cheatham’s Division. It is estimated that between 150 to 300 Confederate wounded were treated at the Goodnight hospital.

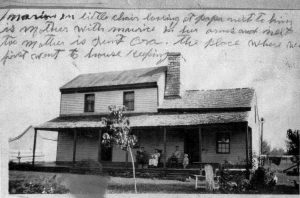

Undated Photograph of the Goodnight House, which was used as a hospital by Confederate troops after the Battle of Perryville.

Private Sam Watkins, who was shot through the hat and cartridge box, was detailed to help bring off the wounded after the battle. According to Private Watkins:

“I was in every battle, skirmish and march that was made by the First Tennessee Regiment during the war, and I do not remember of a harder contest and more evenly fought battle than Perryville.”

Union Colonel John Martin described the scene at the Goodnight hospital:

“As we pressed on evidences of a hasty retreat and flight were manifest. Their dead and wounded were left uncared for, and the ground was covered with guns, blankets and knapsacks, indicating the confusion in which they had fled.”

According to Union Captain Thomas McCahan:

“After dinner Capt. Bell and I started to visit the hospitals, a large farmhouse every room full. Many doctors amputating, a sickening sight. Rebel hospital in the yard was full, men laying in rows. They would lift one, carry him in, amputate, carry him out, and then take another. The sight was too much for me. These legs and arms were thrown out end window, down against a fence handy (to) the building. The pile was higher than the fence.”

Although most of the wounded were sent to Harrodsburg or Danville in the weeks after the battle, the Goodnight farm continued to be used as a hospital through at least December. Of the unknown number of Confederates who died there, many were buried in the Goodnight family cemetery. Lorenzo Goodnight Hankla was 16 years old at the time of the battle, and helped bury the dead. Lorenzo was the grandfather of the current landowners, Ren and Scott Hankla.

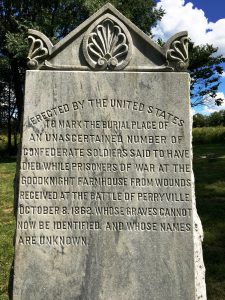

In 1912, 50 years after the battle, the U.S. government sanctioned a monument to the unknown number of Confederates buried in the Goodnight cemetery. The Unknown Confederate Dead Monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997.

Ground Penetrating Radar

The mapping of burials, particularly historical burials, is a challenging task. Without physically stripping the soil away to look for grave shafts, archaeologists must rely on a handful of non-invasive techniques for “seeing” beneath the ground. Several technologies exist that allow us to measure the different geophysical properties of soil. By combining these measurements with a host of historical knowledge and a little bit of luck, we can map the subsurface in a way that allows us to detect patterns and look for evidence of human modification.

One of the most useful techniques for mapping burials is Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). GPR uses an antenna to send pulses of energy deep into the ground. When these radar pulses, or waves, encounter different materials (stone, different soils, water, empty voids), the waves begin to reflect back to the antenna at different speeds. The GPR system records these reflections as it is moved back and forth over the area of interest. The particular strength of the GPR technique is that it can record depth and provide a 3-dimensional view of the target area and any anomalies that it detects.

Once the entire area of interest has been surveyed with the GPR equipment, the data is downloaded and processed using a powerful software program. This allows the data to be visualized in addition to filtering out background noise and amplifying weak signals. The end result is often a very colorful map which displays any anomalies in the data (areas in which the GPR waves reflected differently than in surrounding soil).

Kentucky Heritage Council Archaeology Review Coordinator, Nick Laracuente, multitasking and assisting with the GPR survey.

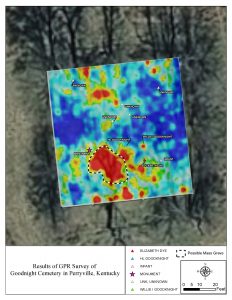

A GPR survey was conducted at the Goodnight Cemetery in an attempt to find the graves of multiple Confederate POW soldiers from the Battle of Perryville. The cemetery is approximately 800 sq. ft. and contains multiple individual family grave plots. Oral tradition holds that as many as 120 Confederate POWs were buried here. If true, the sheer number of bodies in such a small space would almost certainly necessitate the use of one or more mass graves or pits. Indeed, a large pit-like anomaly was detected in the southern portion of the cemetery. In addition to being positioned away from marked burials, oral tradition also holds that the POWs were buried in the southern portion of the Goodnight Cemetery. The GPR results have not been tested or verified, but when combined with the historical record of the cemetery, as well as oral tradition, there is ample evidence to suggest that the POWs were indeed buried in one or more mass graves at the southern portion of the cemetery. Interestingly the Unknown Confederate Dead Monument appears to potentially mark a large, pit-like, subsurface anomaly that may be the mass grave.

Public Archaeology

This project was truly an exercise in public archaeology, and would not have been possible without the interest and cooperation of the Hankla family. The current landowners, Ren and Scott Hankla, are descendants of John Goodnight and his daughter Elizabeth Dye, both of whom are buried in the cemetery.

Several volunteers assisted in this survey, including: Ren, Faye, Scott, and Mary Pat Hankla; Nick, Tiffany, Rosemary, and Sage Laracuente; Morgan Wampler; Jessica Demaree Handshoe; and Michael Robinson. Special thanks goes to Dr. George Crothers at the University of Kentucky for loaning us the GPR equipment, and for meeting with us twice on a Saturday.

Examining the grave markers of Willie I. Goodnight (1859-1860) and Elizabeth Goodnight Dye (1797-1874).